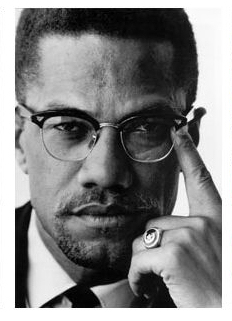

Malcolm X:

"Message To The Grass Roots"

. . . . . . . . . .

To understand this, you have to go back to what the young brother here referred to as the house Negro and the field Negro -- back during slavery. There was two kinds of slaves. There was the house Negro and the field Negro.

The house Negroes -- they lived in the house with master, they dressed pretty good, they ate good 'cause they ate his food -- what he left.

They lived in the attic or the basement, but still they lived near the master; and they loved their master more than the master loved himself. They would give their life to save the master's house quicker than the master would.

The house Negro, if the master said, "We got a good house here," the house Negro would say, "Yeah, we got a good house here." Whenever the master said "we," he said "we." That's how you can tell a house Negro.

If the master's house caught on fire, the house Negro would fight harder to put the blaze out than the master would. If the master got sick, the house Negro would say, "What's the matter, boss, we sick?" We sick! He identified himself with his master more than his master identified with himself.

And if you came to the house Negro and said, "Let's run away, let's escape, let's separate," the house Negro would look at you and say, "Man, you crazy. What you mean, separate? Where is there a better house than this? Where can I wear better clothes than this? Where can I eat better food than this?" That was that house Negro. In those days he was called a "house nigger."

And that's what we call him today, because we've still got some house niggers running around here. This modern house Negro loves his master. He wants to live near him. He'll pay three times as much as the house is worth just to live near his master, and then brag about "I'm the only Negro out here." "I'm the only one on my job." "I'm the only one in this school." You're nothing but a house Negro.

And if someone comes to you right now and says, "Let's separate," you say the same thing that the house Negro said on the plantation. "What you mean, separate from America? This good white man? Where you going to get a better job than you get here?" I mean, this is what you say. "I ain't left nothing in Africa," that's what you say. Why, you left your mind in Africa.

On that same plantation, there was the field Negro. The field Negro -- those were the masses. There were always more Negroes in the field than there was Negroes in the house. The Negro in the field caught hell. He ate leftovers.

The field Negro was beaten from morning to night. He lived in a shack, in a hut; He wore old, castoff clothes. He hated his master. I say he hated his master. He was intelligent. That house Negro loved his master. But that field Negro -- remember, they were in the majority, and they hated the master. When the house caught on fire, he didn't try and put it out; that field Negro prayed for a wind, for a breeze. When the master got sick, the field Negro prayed that he'd die. If someone come to the field Negro and said, "Let's separate, let's run," he didn't say "Where we going?" He'd say, "Any place is better than here." You've got field Negroes in America today. I'm a field Negro. The masses are the field Negroes. When they see this man's house on fire, you don't hear these little Negroes talking about "our government is in trouble." They say, "The government is in trouble."

Imagine a Negro: "Our government"! I even heard one say "our astronauts." They won't even let him near the plant -- and "our astronauts"! "Our Navy" -- that's a Negro that's out of his mind. That's a Negro that's out of his mind. Just as the slavemaster of that day used Tom, the house Negro, to keep the field Negroes in check, the same old slavemaster today has Negroes who are nothing but modern Uncle Toms, 20th century Uncle Toms, to keep you and me in check, keep us under control, keep us passive and peaceful and nonviolent. That's Tom making you nonviolent. It's like when you go to the dentist, and the man's going to take your tooth. You're going to fight him when he starts pulling. So he squirts some stuff in your jaw called novocaine, to make you think they're not doing anything to you. So you sit there and 'cause you've got all of that novocaine in your jaw, you suffer peacefully. Blood running all down your jaw, and you don't know what's happening. 'Cause someone has taught you to suffer -- peacefully.

The white man do the same thing to you in the street, when he wants to put knots on your head and take advantage of you and don't have to be afraid of your fighting back. To keep you from fighting back, he gets these old religious Uncle Toms to teach you and me, just like novocaine, suffer peacefully. Don't stop suffering -- just suffer peacefully. As Reverend Cleage pointed out, "Let your blood flow In the streets." This is a shame. And you know he's a Christian preacher. If it's a shame to him, you know what it is to me.

This is the way it is with the white man in America. He's a wolf and you're sheep. Any time a shepherd, a pastor, teach you and me not to run from the white man and, at the same time, teach us not to fight the white man, he's a traitor to you and me. Don't lay down our life all by itself. No, preserve your life, it's the best thing you got. And if you got to give it up, let it be even-steven.

. . . . . . . . . .

To understand this, you have to go back to what the young brother here referred to as the house Negro and the field Negro -- back during slavery. There was two kinds of slaves. There was the house Negro and the field Negro.

The house Negroes -- they lived in the house with master, they dressed pretty good, they ate good 'cause they ate his food -- what he left.

They lived in the attic or the basement, but still they lived near the master; and they loved their master more than the master loved himself. They would give their life to save the master's house quicker than the master would.

The house Negro, if the master said, "We got a good house here," the house Negro would say, "Yeah, we got a good house here." Whenever the master said "we," he said "we." That's how you can tell a house Negro.

If the master's house caught on fire, the house Negro would fight harder to put the blaze out than the master would. If the master got sick, the house Negro would say, "What's the matter, boss, we sick?" We sick! He identified himself with his master more than his master identified with himself.

And if you came to the house Negro and said, "Let's run away, let's escape, let's separate," the house Negro would look at you and say, "Man, you crazy. What you mean, separate? Where is there a better house than this? Where can I wear better clothes than this? Where can I eat better food than this?" That was that house Negro. In those days he was called a "house nigger."

And that's what we call him today, because we've still got some house niggers running around here. This modern house Negro loves his master. He wants to live near him. He'll pay three times as much as the house is worth just to live near his master, and then brag about "I'm the only Negro out here." "I'm the only one on my job." "I'm the only one in this school." You're nothing but a house Negro.

And if someone comes to you right now and says, "Let's separate," you say the same thing that the house Negro said on the plantation. "What you mean, separate from America? This good white man? Where you going to get a better job than you get here?" I mean, this is what you say. "I ain't left nothing in Africa," that's what you say. Why, you left your mind in Africa.

On that same plantation, there was the field Negro. The field Negro -- those were the masses. There were always more Negroes in the field than there was Negroes in the house. The Negro in the field caught hell. He ate leftovers.

The field Negro was beaten from morning to night. He lived in a shack, in a hut; He wore old, castoff clothes. He hated his master. I say he hated his master. He was intelligent. That house Negro loved his master. But that field Negro -- remember, they were in the majority, and they hated the master. When the house caught on fire, he didn't try and put it out; that field Negro prayed for a wind, for a breeze. When the master got sick, the field Negro prayed that he'd die. If someone come to the field Negro and said, "Let's separate, let's run," he didn't say "Where we going?" He'd say, "Any place is better than here." You've got field Negroes in America today. I'm a field Negro. The masses are the field Negroes. When they see this man's house on fire, you don't hear these little Negroes talking about "our government is in trouble." They say, "The government is in trouble."

Imagine a Negro: "Our government"! I even heard one say "our astronauts." They won't even let him near the plant -- and "our astronauts"! "Our Navy" -- that's a Negro that's out of his mind. That's a Negro that's out of his mind. Just as the slavemaster of that day used Tom, the house Negro, to keep the field Negroes in check, the same old slavemaster today has Negroes who are nothing but modern Uncle Toms, 20th century Uncle Toms, to keep you and me in check, keep us under control, keep us passive and peaceful and nonviolent. That's Tom making you nonviolent. It's like when you go to the dentist, and the man's going to take your tooth. You're going to fight him when he starts pulling. So he squirts some stuff in your jaw called novocaine, to make you think they're not doing anything to you. So you sit there and 'cause you've got all of that novocaine in your jaw, you suffer peacefully. Blood running all down your jaw, and you don't know what's happening. 'Cause someone has taught you to suffer -- peacefully.

The white man do the same thing to you in the street, when he wants to put knots on your head and take advantage of you and don't have to be afraid of your fighting back. To keep you from fighting back, he gets these old religious Uncle Toms to teach you and me, just like novocaine, suffer peacefully. Don't stop suffering -- just suffer peacefully. As Reverend Cleage pointed out, "Let your blood flow In the streets." This is a shame. And you know he's a Christian preacher. If it's a shame to him, you know what it is to me.

This is the way it is with the white man in America. He's a wolf and you're sheep. Any time a shepherd, a pastor, teach you and me not to run from the white man and, at the same time, teach us not to fight the white man, he's a traitor to you and me. Don't lay down our life all by itself. No, preserve your life, it's the best thing you got. And if you got to give it up, let it be even-steven.

. . . . . . . . . .

Biography:

Malcolm X (1925 - 1965)

African American civil rights leader, was a major 20th-century spokesman

for black nationalism.

Malcolm X was born Malcolm Little on May 19, 1925, in Omaha, Nebr. His father, a minister, was an outspoken follower of Marcus Garvey, the black nationalist leader in the 1920s who advocated a "back-to-Africa" movement for African Americans. During Malcolm's early years his family moved several times because they were threatened by Ku Klux Klansmen in Omaha; their home was burned in Michigan; and when Malcolm was 6 years old, his father was murdered. For a time his mother and her eight children lived on public welfare. When his mother became mentally ill, Malcolm was sent to a foster home. His mother remained in a mental institution for about 26 years. The children were divided among several families, and Malcolm lived in various state institutions and boarding-houses. He dropped out of school at the age of 15. Living with his sister in Boston, Malcolm worked as a shoeshine boy, soda jerk, busboy, waiter, and railroad dining car waiter. At this point he began a criminal life that included gambling, selling drugs, burglary, and hustling.

In 1946 Malcolm was sentenced to 10 years for burglary. In prison he began to transform his life. His family visited and wrote to him about the Black Muslim religious movement. (The Black Muslims' official name was the Lost-Found Nation of Islam, and the spiritual leader was Elijah Muhammad, with national headquarters in Chicago.) Malcolm began to study Muhammad's teachings and to practice the religion faithfully. In addition, he enlarged his vocabulary by copying words from the dictionary, beginning with "A" and going through to "Z." He began to assimilate the racial teachings of his new religion; that the white man is evil, doomed by Allah to destruction, and that the best course for black people is to separate themselves from Western, white civilization--culturally, politically, physically, psychologically.

In 1952 Malcolm was released from prison and went to Chicago to meet Elijah Muhammad. Accepted into the movement and given the name of Malcolm X, he became assistant minister of the Detroit Mosque. The following year he returned to Chicago to study personally under Muhammad and shortly thereafter was sent to organize a mosque in Philadelphia. In 1954 he went to lead the mosque in Harlem.

Malcolm X became the most prominent national spokesman for the Black Muslims. He was widely sought as a speaker, and his debating talents against white and black opponents helped spread the movement's message. At this time in the United States there was a major thrust for racial integration; however, Malcolm X and the Black Muslims were calling for racial separation. He believed that the civil rights gains made in America were only tokenism. He castigated those African Americans who used the tactic of nonviolence in order to achieve integration and advocated self-defense in the face of white violence. He urged black people to give up the Christian religion, reject integration, and understand that the high crime rate in black communities was essentially a result of African Americans following the decadent mores of Western, white society. During this period Malcolm X, following Elijah Muhammad, urged black people not to participate in elections because to do so meant to sanction the immoral political system of the United States.

In 1957 Malcolm X met a young student nurse in New York; she shortly became a member of the Black Muslims, and they were married in 1958; they had six daughters. For at least two years before 1963, some observers felt that there were elements within the Black Muslim movement that wanted to oust Malcolm X. There were rumors that he was building a personal power base to succeed Elijah Muhammad and that he wanted to make the organization political. Others felt that the personal jealousy of some Black Muslim leaders was a factor.

On Dec. 1, 1963, Malcolm X stated that he saw President John F. Kennedy's assassination as a case of "The chickens coming home to roost." Soon afterward Elijah Muhammad suspended him and ordered him not to speak for the movement for 90 days. On March 8, 1964, Malcolm X publicly announced that he was leaving the Nation of Islam and starting two new organizations: the Muslim Mosque, Inc., and the Organization of Afro-American Unity. He remained a believer in the Islamic religion.

During the next months Malcolm X made several trips to Africa and Europe and one to Mecca. Based on these, he wrote that he no longer believed that all white people were evil and that he had found the true meaning of the Islamic religion. He changed his name to El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz. He announced that he planned to internationalize the black struggle by taking black people's complaints against the United States before the United Nations. For this purpose he sought aid from several African countries through the Organization of Afro-American Unity. At the same time he stated that his organizations were willing to work with other black organizations and with progressive white groups in the United States on voter registration, on black control of community public institutions such as schools and the police, and on other civil and political rights for black people. He began holding meetings in Harlem at which he enunciated the policies and programs of his new organizations. On a Sunday afternoon, Feb. 21, 1965, as he began to address one such meeting, Malcolm X was assassinated.

Since his death Malcolm X's influence on the political and social thinking of African Americans has been enormous, and the literature about him has proliferated. Malcolm X Community College in Chicago, Malcolm X Liberation University in Durham, N.C., and the Malcolm X Society are named for him.

Malcolm X was born Malcolm Little on May 19, 1925, in Omaha, Nebr. His father, a minister, was an outspoken follower of Marcus Garvey, the black nationalist leader in the 1920s who advocated a "back-to-Africa" movement for African Americans. During Malcolm's early years his family moved several times because they were threatened by Ku Klux Klansmen in Omaha; their home was burned in Michigan; and when Malcolm was 6 years old, his father was murdered. For a time his mother and her eight children lived on public welfare. When his mother became mentally ill, Malcolm was sent to a foster home. His mother remained in a mental institution for about 26 years. The children were divided among several families, and Malcolm lived in various state institutions and boarding-houses. He dropped out of school at the age of 15. Living with his sister in Boston, Malcolm worked as a shoeshine boy, soda jerk, busboy, waiter, and railroad dining car waiter. At this point he began a criminal life that included gambling, selling drugs, burglary, and hustling.

In 1946 Malcolm was sentenced to 10 years for burglary. In prison he began to transform his life. His family visited and wrote to him about the Black Muslim religious movement. (The Black Muslims' official name was the Lost-Found Nation of Islam, and the spiritual leader was Elijah Muhammad, with national headquarters in Chicago.) Malcolm began to study Muhammad's teachings and to practice the religion faithfully. In addition, he enlarged his vocabulary by copying words from the dictionary, beginning with "A" and going through to "Z." He began to assimilate the racial teachings of his new religion; that the white man is evil, doomed by Allah to destruction, and that the best course for black people is to separate themselves from Western, white civilization--culturally, politically, physically, psychologically.

In 1952 Malcolm was released from prison and went to Chicago to meet Elijah Muhammad. Accepted into the movement and given the name of Malcolm X, he became assistant minister of the Detroit Mosque. The following year he returned to Chicago to study personally under Muhammad and shortly thereafter was sent to organize a mosque in Philadelphia. In 1954 he went to lead the mosque in Harlem.

Malcolm X became the most prominent national spokesman for the Black Muslims. He was widely sought as a speaker, and his debating talents against white and black opponents helped spread the movement's message. At this time in the United States there was a major thrust for racial integration; however, Malcolm X and the Black Muslims were calling for racial separation. He believed that the civil rights gains made in America were only tokenism. He castigated those African Americans who used the tactic of nonviolence in order to achieve integration and advocated self-defense in the face of white violence. He urged black people to give up the Christian religion, reject integration, and understand that the high crime rate in black communities was essentially a result of African Americans following the decadent mores of Western, white society. During this period Malcolm X, following Elijah Muhammad, urged black people not to participate in elections because to do so meant to sanction the immoral political system of the United States.

In 1957 Malcolm X met a young student nurse in New York; she shortly became a member of the Black Muslims, and they were married in 1958; they had six daughters. For at least two years before 1963, some observers felt that there were elements within the Black Muslim movement that wanted to oust Malcolm X. There were rumors that he was building a personal power base to succeed Elijah Muhammad and that he wanted to make the organization political. Others felt that the personal jealousy of some Black Muslim leaders was a factor.

On Dec. 1, 1963, Malcolm X stated that he saw President John F. Kennedy's assassination as a case of "The chickens coming home to roost." Soon afterward Elijah Muhammad suspended him and ordered him not to speak for the movement for 90 days. On March 8, 1964, Malcolm X publicly announced that he was leaving the Nation of Islam and starting two new organizations: the Muslim Mosque, Inc., and the Organization of Afro-American Unity. He remained a believer in the Islamic religion.

During the next months Malcolm X made several trips to Africa and Europe and one to Mecca. Based on these, he wrote that he no longer believed that all white people were evil and that he had found the true meaning of the Islamic religion. He changed his name to El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz. He announced that he planned to internationalize the black struggle by taking black people's complaints against the United States before the United Nations. For this purpose he sought aid from several African countries through the Organization of Afro-American Unity. At the same time he stated that his organizations were willing to work with other black organizations and with progressive white groups in the United States on voter registration, on black control of community public institutions such as schools and the police, and on other civil and political rights for black people. He began holding meetings in Harlem at which he enunciated the policies and programs of his new organizations. On a Sunday afternoon, Feb. 21, 1965, as he began to address one such meeting, Malcolm X was assassinated.

Since his death Malcolm X's influence on the political and social thinking of African Americans has been enormous, and the literature about him has proliferated. Malcolm X Community College in Chicago, Malcolm X Liberation University in Durham, N.C., and the Malcolm X Society are named for him.

© Herbert Paukert